Introduction

For our narrative, we wanted to ensure that the young people were driving the creative process. Therefore, our output became a very visual piece, a scrapbook of our work, ideas, and artwork. The following is a written version of our scrapbook narrative, it is conversational in style because it aims to tell the ‘story’ of our project – the process of what we did, how we worked together and what we tried to achieve. You can view the scrapbook here.

UK_narrative_artistic_productionOur Starting Point

The Manchester Team consists of academics, creatives and activists who are all members of Refugee and Asylum Participatory Action Research or better known as ‘RAPAR’ a Manchester-based human rights organisation. ‘Opening Universities for Youth in Europe’ (OUYE) is an Erasmus+ project that aims to enhance access to higher education for marginalised groups. However, in the UK, migrants, refugees and those seeking asylum have difficulty accessing even basic services as successive governments have introduced policies that have systematically eroded their human rights. Until displaced people achieve ‘legal’ status here, they cannot access higher education. Therefore from the outset of the project, we avoided thinking of ‘access’ to universities in conventional terms.

Manchester is a thriving city rich in culture. However, like the university, many educational and cultural institutions are inaccessible and unresponsive to the diverse communities that live in Manchester. This means that many marginalised groups – such as migrants, refugees and asylum seekers – feel like these places are ‘not for them’. They do not get invited to such spaces and at times are actively excluded from them.

In this way, marginalised voices are not heard within processes of cultural, democratic and social change, and many groups feel invisible, ignored, and without hope or any sense of belonging. RAPAR, alongside other organisations in Manchester, has a long history of campaigning and activism supporting the rights and active participation of migrants in the city.

To begin understanding these issues of exclusion, we explored an often taken-for-granted attachment to where one lives – a ‘belonging’. We started with the question ‘Where do we belong?’ in order to foreground a sense of belonging somewhere or anywhere. We started to explore Manchester together, including its cultural institutions and the university, to rethink ‘belonging’ and to start a process of meaning-making around rights, recognition, and cultural, democratic and social change.

Stage One: Autumn/Winter 2021

Unlike other teams in OUYE, we didn’t have an established group of young people to participate so we issued an invitation flyer through our networks. We ran the first workshops at Brooks, which is part of the Manchester Metropolitan University campus.

However, we quickly learned that the space was not very inviting or cosy… but it was free!

Shortly after we ran a few workshops, another wave of COVID-19 began and infection rates rose. Therefore, we had to stop meeting in person and instead move the workshops online.

Our First Workshops

During the sessions at Brooks, we played games to get to know one another, and we also started to think about what we wanted to do during the project, such as what it would be about and what we wanted to achieve.

We used Participatory Action Research as our methodological approach, which emphasises the importance of process and ‘starting where young people are’. This approach allows for flexibility and creativity, for ideas to emerge over time,

and for different voices to be heard. This is particularly important when working with those who are already marginalised and dismissed. This deliberately unstructured approach gave the young people time and space to explore on their own terms.

We hoped that over time, rather than the ‘adults’ leading the sessions, the young people would feel able to direct and lead the project. But first, we knew that we would have to build a relationship of trust with them.

Artistic Output 1

As COVID-19 rates rose, and we all got ill too, we had to move our work online and rethink the proposed content of some sessions. Previously, the young people had mentioned that they wanted to unpick several contested terms with us. To begin this process, we asked the young people what they understood by terms such as ‘white supremacy’, ‘imperialism’, ‘colonialism’ and so forth. We also asked the young people about what these terms meant in their daily lives.

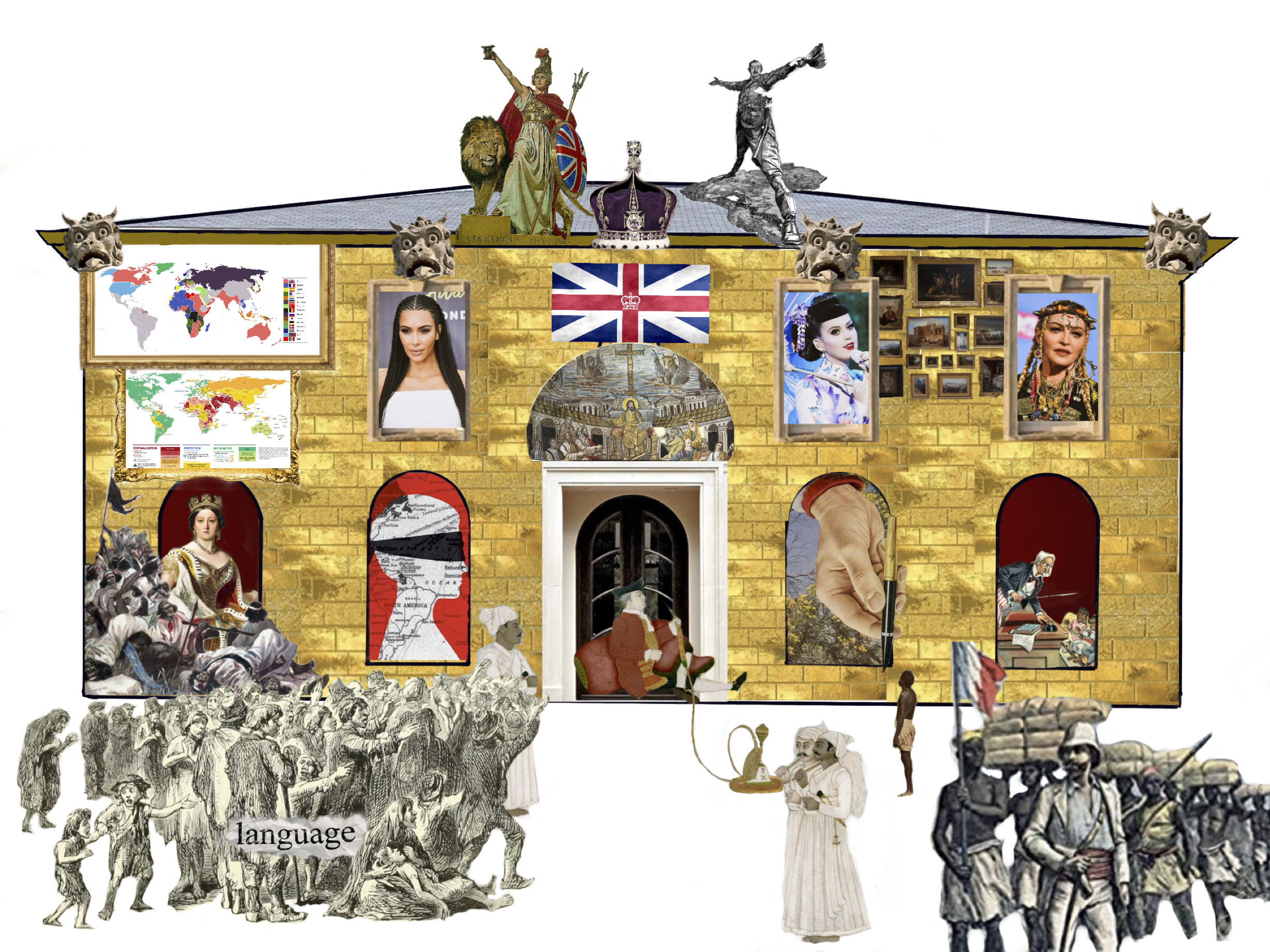

From this discussion we created our first artistic output: Colonial House.

Every image that makes up this collage was sent in by the participants and represents what ‘colonialism’ means to them. Images include depictions of cultural appropriation, famine, language, education, and the British Empire.

Stage Two: Spring 2022

As the weather got warmer and the rate of COVID- 19 infections started to fall, we started to do walking tours of the city. We bought disposable cameras and took photos of places that interested us. As we had a limited amount of photos we could take, and we had to wait for them to be developed, we carefully considered what we took photos of and why.

This process stimulated conversations about the city, what we saw, places we knew or did not know, places we liked or didn’t like, and places where we felt welcome or not.

The young people commented about how the act of walking around the city helped to make them feel a greater sense of belonging in Manchester.

Workshops in the RAPAR Office

The RAPAR office is in Central Manchester, it is a much more welcoming space than the university. The location also allowed us to do some sessions there and some exploring the city depending on the weather.

Throughout the project, we found that it was much easier to encourage discussion when the group members were working on other things at the same time. This is part of our approach to learning together by doing, talking and reflecting.

This is why in the RAPAR office we worked with the young people to get creative!

We had paints, paper, pencils and an array of art equipment. Getting creative meant that we could all work on our own pieces whilst reflecting on what we were doing, and have conversations about the project. We found that this was a much more informal, open and comfortable approach, and worked well.

Exploring Manchester

We also spent many sessions exploring different parts of Manchester, walking through the streets together, laughing, joking and getting to know each other. We stopped to take photographs and to get something to eat. We talked about different things we noticed, buildings we came across and parts of the city where we had not been before.

We wanted to visit galleries and museums, but they were often closed in the evenings. One of the places that was open, however, and full of young people, was the ‘central library’. It has lots of exhibitions and displays about the history of Manchester.

St Peter’s Square – a busy part of the city – is directly in front of the library and is where lots of demonstrations and street protests take place. It is not far from the site of The Peterloo Massacre where a crowd of 60,000 gathered in 1819 to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. The authorities charged in on horses to disperse the protestors, resulting in many injuries and death.

The square has recently been regenerated; it is surrounded by office blocks and one of the new features is very expensive blossom trees. There is a mix of people – middle-class business people, office workers, people getting the tram, and people enjoying the several bars and cafes around. Kids like to skateboard there, and homeless people often hang around because the adjacent library has one of the only free and accessible public toilets left in the city.

After making notes and observing the happenings and people in St. Peter’s

Square, we decided to compare it with Piccadilly Gardens where we had spent

time before. We spent a lovely sunny afternoon sitting in Piccadilly Gardens, which felt alive with all the different cultures and communities living in the city coming together – it felt much more diverse and welcoming to everyone than austere St. Peter’s Square. Frequently, human rights protests and other demonstrations take place in Piccadilly Gardens too.

There is a children’s playground and water fountains, and many people sit around enjoying takeaway food, which is more available and less expensive than the restaurants in St. Peter’s Square. The atmosphere is generally convivial, and there is little shelter from the (frequent!) rain. Usually, only those who tend to be unable to access places in the city where you need spending money congregate there. Piccadilly Gardens has a history of being a place for the ‘other’ – in the 17/1800s it was the site of an old asylum for the mentally ill. However, though it is relaxed, it does not always feel friendly and safe, and we talked about how sometimes ‘Piccadilly’ feels unsafe, smells of urine, and feels full of pollution from the nearby bus station.

We started to think about what Piccadilly Gardens could be if we had the chance to reimagine it.

We also explored other parts of the city such as Castlefield. Some of us had not been here before even though it is close to the city centre. The flats are expensive but historically, Castlefield was an industrial area and home to the canal network that was important for transporting goods in and out of the city. The bridges over the canals and the small canal paths that intersect with one another create a maze of possibilities to explore and view the city from different angles and levels. When we visited, we enjoyed taking videos of each other walking across the bridges at different levels. On the day we visited, the sunlight was also beautiful and it created interesting shadows. We started to feel like we were less in the shadows and more in the light. We talked about belonging.

From there, we visited Media City, home to part of the BBC – the world’s oldest broadcaster. We got a tram because it is too far to walk – we all enjoyed getting the tram because most of us use the bus or cycle. The tram is expensive.

Like Castlefield, Media City is also an old industrial site; the docklands are no longer used to transport produce but now give much-needed tranquility and a feeling of space close to the hectic city centre.

We visited the Lowry Museum, home to many paintings by L.S. Lowry who lived and painted in the area at the turn of the century. He is famous for painting ‘matchstick’ figures because he tended to paint people at a distance. He often felt like an outsider himself and like he didn’t belong even though he lived his whole life in the same area. This made us rethink some assumptions we had about who might automatically feel a sense of belonging to a place.

Stage Three: Summer 2022

After exploring Manchester, we then came back to the RAPAR office. We started to think about reimagining the city to help create a sense of belonging for others. We wanted to use our imaginations and think about what could be possible. We came across the idea of ‘utopia’ and started to look at other examples of utopian cities around the world. We looked at the history of the word ‘utopia’ coined by Thomas More in 1516, derived from the Greek ou-topos, which means ‘no place’ or ‘nowhere’. It also refers to eu-topos, meaning ‘a good place’. Utopias are often imaginary and are an ideal of perfection and happiness. They feel possible and impossible at the same time.

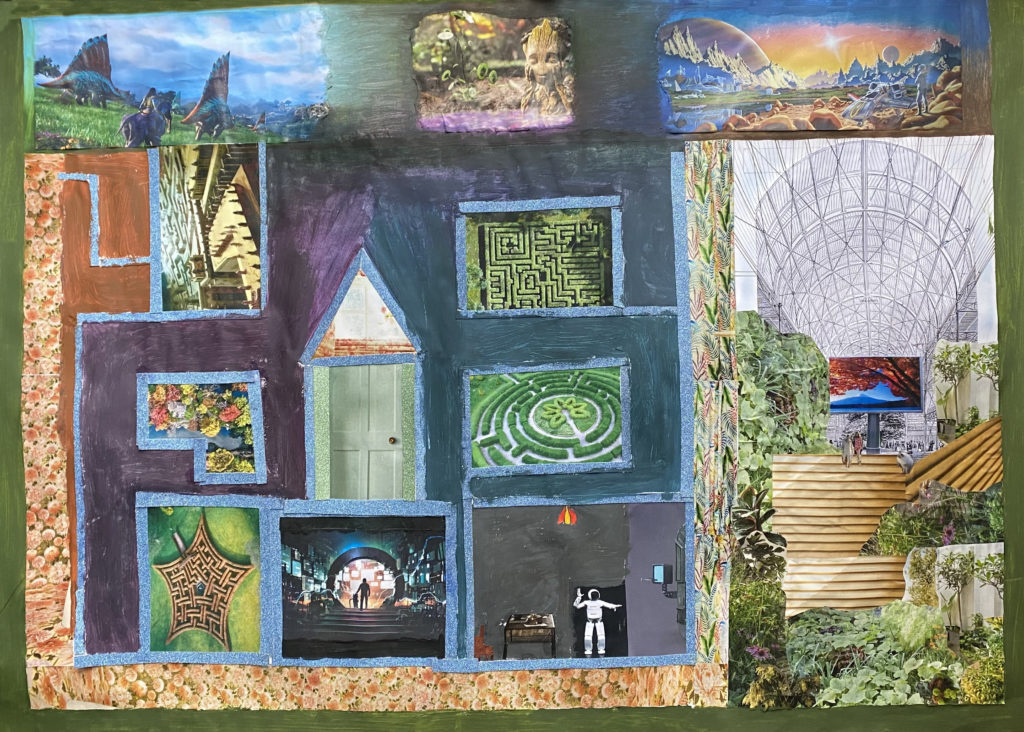

We decided to reimagine Piccadilly Gardens as a utopian space and produced our second artistic production imagining what this would look like.

Our Utopian Piccadilly Gardens consists of many different areas to try to foster spaces of belonging and community for everyone. In the main atrium or community space, there is a glass roof, a stage where groups can perform, and a billboard that rather than telling you what to buy, aims to inspire what you could be. Sometimes films or music are played and it is free for people to use how they want. People also cook and share food, we grow vegetables outside, and people can enjoy the flora and fauna growing on the roof.

The Maze of Possibilities is a secret place that exists there too for those who dare to enter. You can access it through the main atrium, occasionally on the billboard the Maze of Possibilities is advertised to entice members of the public to try out the experience. First, they must take a lie detector test administered by a robot to see if they have good intentions. If they pass, they can then choose to walk through one of the doors and have a new experience that may teach them something that they can use for their own personal development or for the good of others. For example, a rich, privileged person could go through a door to experience what it is like to be poor. We discussed how creating possibilities for others to ‘step inside someone’s shoes’ might create ripples of social change that we would like to see in the city. We think our Utopian Piccadilly Gardens could allow for communities to come together to address various social justice issues together.

For output three of the OUYE project, we plan to continue to explore these ideas as part of our seminar series.